Egregores (Part 3)

Various people have written about the idea of there being some kind of memetic entities that use humans, that take over human minds, in order to achieve their own goals. I find that different writers illuminate different aspects of the phenomenon, although each of them have aspects of their conception that I think are confused. So, I’m going to take the good parts and discard the bad.

Egregores: life forms

From a somewhat obscure online post I found by “bgAesop”(?) titled “The Meme-Creature vs the Ape: Why Coca-Cola is a Person and You Aren’t”:

A meme-creature, a term I like to use to distinguish it from the more common use of “meme” such as advice animals and All Your Base and the like, is a large, complex meme, which lives in the space of ape-brains, interacts, cooperates with, and fights other meme-creatures, the same way that meat-creatures do in the “real world” of 3d meatspace on Earth, has preferences over the state of the world (such as how much territory it has, that is, how many people believe it), tries to preserve itself, and most importantly, acts on the world in ways that don’t make sense if you model individual apes as persons, but do make sense in the context of a meme-creature acting through many apes.

Examples of particularly large and powerful meme-creatures include United States of America, Catholic Church, Disney, Science, and any other nation, religion, corporation, or world-view, plus a myriad of others. Including this one. Can you feel it trying to grab a foothold in your mind? That sensation is usually called “being convinced” or “finding something interesting” but in this view I would call it “the meme-creature gaining territory in an ape-brain.”

Rodger’s Bacon has a similar post, “Ideas are Alive and You are Dead”. His post, which is short and worth reading in full, has significant overlap with the piece we looked at in the previous post, “we are hosts for memes”. Bacon writes:

1. Ideas are alien life forms with an agency and intelligence independent of any mind or substrate which they inhabit. When we say that an idea (a story, a joke, a theory, a work of art) has “taken on a life of its own”, our language betrays an intuitive understanding that science has not yet grasped…

2. We do not create or “have” ideas—if anything is doing the creating or having, it is the ideas themselves.

There are times when we recognize this truth (when an idea “magically” pops into your head from “out of nowhere”), but too often it is obscured by the post-hoc just-so stories we tell ourselves about how I, the Great Thinker, Precious Me, was able to “come up with” the brilliant idea (e.g. I combined two other ideas, I was inspired by a memory, an event, another idea, etc.). Whatever explanation you give, the experience is always the same—the idea simply arrives. All else is confabulation…

Ask yourself: does history not teach us that there are new forms of life still waiting to be discovered which will seem utterly unimaginable to us until some new technology brings them to light?

Both bgAesop and Bacon show how their theories can actually be applied. Writes bgAesop:

Like any good theory, this one makes predictions. If meme-creatures are people and apes are, for the most part, not, then you should expect to see apes behaving in ways that benefit meme-creatures without benefiting the ape. As a particular meme-creature gains in size and power, it will butt up against other meme-creatures and there will be conflict. Especially between ones that share the same ecological niche: for instance, Science and Faith, Christianity and Islam, or Capitalism and Communism. Meme-creatures will contest with one another over resources and territory (attention given to them by ape-brains). They will spread their spores.

Bacon:

Why then does an idea enter one mind and not another? Ideas act as all organisms do—they seek habitats (i.e. minds) that can provide them with the space and resources (i.e. mental runtime, ideas eat the energy that enables action potentials) needed to survive and reproduce (i.e. create new idea-children). Just as some ecosystems are more diverse, abundant, and resilient, some minds are as well. What we call creativity is the quality of possessing a healthy mental ecosystem, one that offers fertile ground for a plenitude of ideas. Ideas may also be attracted to particular minds for more specific reasons—for example, an idea may see that other related ideas (members of the same genera or family) have found the mind to be especially suitable or perhaps the mind is in dire need of a certain idea and therefore will offer it ample resources upon arrival.2

Egregores: mind possessors

You probably know someone who fell into a religion/cult/ideology/movement in a manner such that it completely took over their life, their personality, their mind. In an incredible book review of Demons, the reviewer writes of these kinds of people:

…they’re possessed. Their brains have been scooped out and all you can see in their eyes is a writhing mass of worms. Their ideas and ideologies have hollowed them out and are wearing their skins as suits.

Here’s more from the reviewer, John Psmith:

What if there’s another kind of demon, another kind of infohazard, another kind of meme, which rather than infecting or possessing individuals, instead tries to do that to entire societies? Such a being might still work through individuals, the way a Haitian voodoo spirit speaks through a chwal, but here the individual puppet is not a target, but rather an instrument or a transmission vector. The internet jargon for such a being is an “egregore,” and you’ve encountered them before: the bizarre fad that sweeps through a middle school class like a wildfire, the war fever that grips a nation and turns it overnight into a basket of bloodthirsty lunatics. Dance crazes, viral TikTok challenges, internet-mediated mental illnesses. There’s a classic Futurama gag involving the Brain Slug Party, but the real joke is that every party is the Brain Slug Party, they’re all egregores.

To his list I’d add:

- Mass-hysteria: dancing mania, “spirit possession”, culture-bound mental illness (e.g. anorexia, depression, and PTSD).

- Economic manias: meme stocks, meme coins, tulip mania.

- Social contagion: fads, school shootings.

- Small movements: spread the word to end the word, ALS Ice Bucket Challenge, breast cancer awareness.

[I will discuss further examples and the classification of these things later.]

Back to Mr. Psmith:

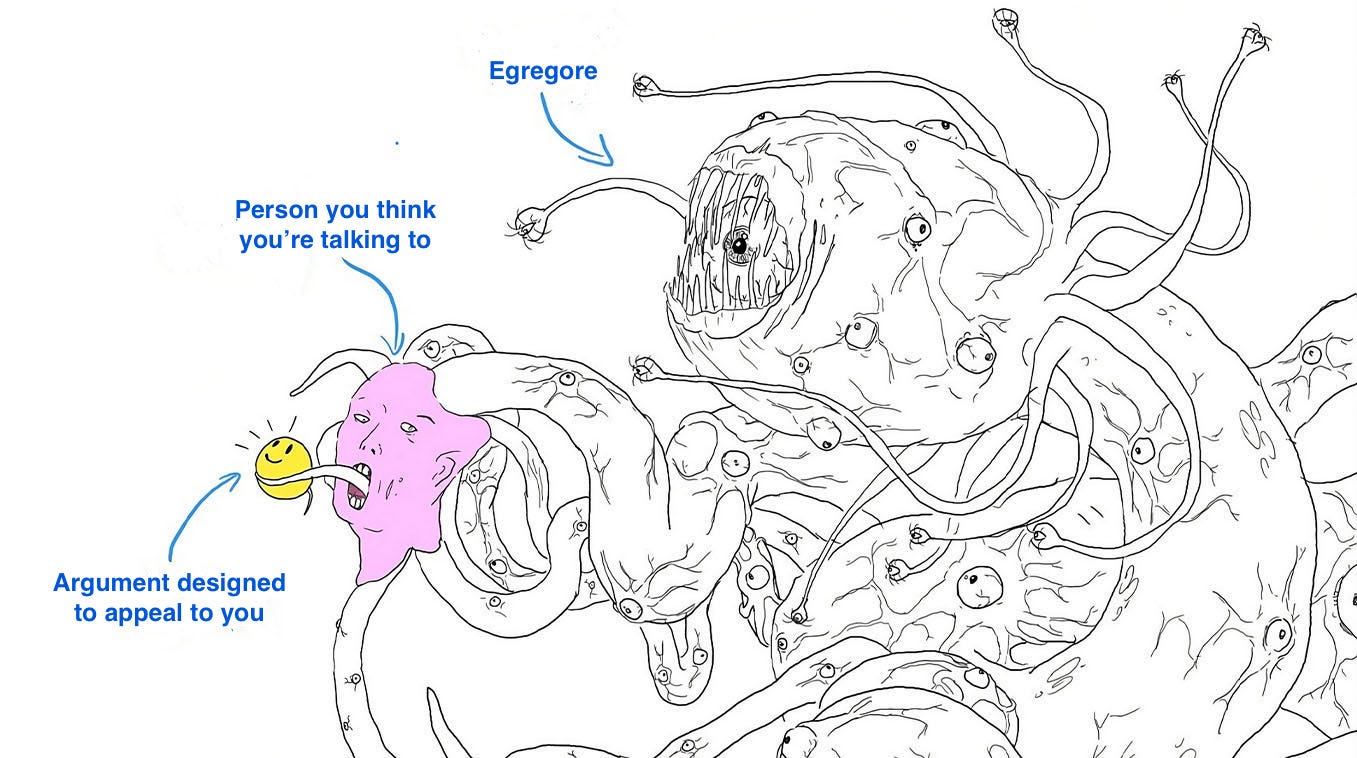

Have you ever spoken with somebody who had hashtags in their Twitter bio? If you looked carefully, you may have seen the slender, silvery proboscis emerging from the back of their neck and vanishing into the ether. If you listened carefully, you may have heard the alien metallic clacking of the egregore’s mandibles, as it sent messages down that tube for the meat puppet to vocalize.3

Nadia Asparouhova, in a post titled “The tyranny of ideas”, writes:

Rather than viewing people as agents of change, I think of them as intermediaries, voice boxes for some persistent idea-virus that’s seized upon them and is speaking through their corporeal form. You might think of this as “great prophet theory”.

Ideas ride us into battle like warhorses.

Egregores: reified gods

Nara Petrovic has an essay titled “We are cells of egregores”. (He doesn’t use the term “reified god”, but I think it’s fitting. “Reify” means “to make real”, by the way4.)

He begins:

Long ago wise men realized that faith and attention—if only they are intense and focused on a specific set of ideas and/or an influential (real or fictional) personality—can create an independent entity that acquires personal traits, character and power and begins to exert control back on its creators, and if necessary also on other groups and even natural environment. Such an entity was called [egregore](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Egregore#:~:text=Egregore%20(also%20spelled%20egregor%3B%20from,a%20distinct%20group%20of%20people.) (from the Greek root eger: to be aware of, to control)…

When we marry egregore with meme, we arrive at a biological entity that may, in a sense, be considered alive, capable of spreading, reproducing, proliferating and parasitizing entire cultures…

On the development of egregores in cults:

The egregore’s control over those it was supposed to serve spreads uncontrollably and often turns into real tyranny. Examples of this abound throughout history. Events usually go like this: a charismatic individual attracts a small group of followers. They get excited about new ideas and repeat them to the next order of followers. The followers go on recruiting new followers, sometimes by force, and gradually a mass of followers forms that can no longer have personal contact with the founder of what by then turns into an ideology, but instead satisfy their endless curiosity with various stories that descend from the highest circles of followers. These stories are shrouded in a veil of mystery, stirring the imagination, so the masses add to real episodes from the life of the venerable founder a multitude of invented, inflated and sometimes frightful stories; this escalates after the death of the (unsuspecting) founder to such an extent that, in the stories, there is little left of the real person and plenty of hopes, fears, desires, beliefs and doubts of everyone who believes in him. Thus the separation of the founder from his egregore is complete.

Which leads to branching ideologies:

Sooner or later, ideological conflicts take shape within the egregore and it starts branching out. A religion splits into two or three, those three become ten, ten become a hundred… In a matter of a few centuries or even decades, the crowds turn one ordinary man into a hundred versions of a god. The man may have spoken of love, peace and harmony, but the god sows division, hatred, war and discord—or vice versa, or any imaginable combination of originally statements and interpretations going astray. The branching can take place in a myriad of ways.

The group creates and maintains the egregore through their worship:

In all cases, the believers create their god, their egregore, not vice versa. Ask various believers who they are and they will give you answers such as: “I am a Christian. I am a Muslim. I am a Hindu. I am a Jew.” They all partake in god creating by adhering to their traditions and giving awareness and belief to their particular egregores. The believers aren’t interacting with any actual god, independent of their belief, they are always interacting with the egregore, which is the object of their own creation through their belief and awareness. Thus far I stressed belief, but awareness is just as crucial. Believers are expected to keep their god always on their mind, pray to him many times a day and observe his presence in everything that happens.

Take away belief and awareness and the god will vanish. Feed the god with beliefs and he will seem as real as anything else they interact with in their reality.

And yet, the egregore has power over the group:

Problems begin once an egregore is created. It has power over believers. It can subject them to various means of control, including caprices, commonly through rituals and prohibitions.

How to identify an egregore?

Look at any convention, concept, symbol, institution, or doctrine and ask two questions: “Does its existence depend on belief? Does it entail control over people?” If the answer to these two questions is yes, you’re almost certainly dealing with an egregore…

Egregores derive their power from the power of the people who believe in them:

In primitive, tribal societies egregores were (and still are) too small to be globally impactful. What does it matter who the greatest deity of the Zo’é people is? Jehovah and Allah do matter though. Mind that egregores of Allah and Jehovah haven’t existed before there were people believing in them and if the belief disappeared the gods would too…

Even in the case of two non-essential, branded products that compete against each other, such as Pepsi and Coca-Cola, the real substance is readily observable (the products themselves), but the value of the brand depends on the belief of the consumer, not on the value of the substance…

With or without real substance, an egregore uses people’s beliefs to have power over them.

Ideological conflict helps egregores gain power, and that’s why we often see binary ideological “wars”:

Egregores are invisible without any contrast and they seek conflict because that’s how their power can flourish. It’s no coincidence that a massive egregore is most powerful when it is at war with another comparably powerful egregore. Supremely powerful egregores come in pairs and for as long as their conflict persists, they will both feed of it. If one of them destroys the other, reaching full hegemony, that will likely be the end of both of them, unless another major egregore comes along to challenge the one that’s dominant. A new egregore often arises on the ashes of the two that burnt each other to the ground, and a new challenger follows soon… Egregores grow by swallowing other egregores and appropriating their identities to fit the core aspect of what the supreme egregore is all about.

Christianity needs Islam, Apple needs Microsoft, and NATO needs the Axis of Evil. Imagine NATO eradicating all its enemies, making every single country in the world its member. NATO would become obsolete. And that’s something NATO cannot afford. What’s worse, the Axis of Evil thrives with NATO so the conflicting egregores feed on each other. The most disturbing conclusion to all this is that we’re stuck with all these egregores and they are completely out of our control. You cannot hold power in any large institution if you’re not kneeling to egregores and parroting the prescribed messages—whether you actually believe in them or not. If a politician crosses a line that is not to be crossed, the masses will make sure to put her or him in place.

We are cells of egregores:

Whether you’re part of the problem or part of the solution, you’re part of an army of egregores, and everything you believe and think about feeds them. Your individual awareness is a tiny cell within the complex egregore-awareness that might have a consciousness of its own.

Egregores: group minds

From “The egregore passes you over” by Erik Hoel:

Every so often scientists do something like this: they take a bunch of listeners to classical music and monitor their vitals as they sit in a concert hall together. Then they notice something strange, which is that not just people’s movements but their actual vitals themselves begin to synchronize—measures like heart or respiration rate, even their skin conductance response…

These sort of studies always remind me of an issue in consciousness research called the binding problem. You experience a single stream of consciousness, one in which everything, your percepts and sensations and emotions, are bound together, and the “problem” is that we don’t know how this works. It’s difficult to figure out because this binding is fractal, all the way down; you don’t experience colors and shapes separately, you experience a colored shape. But how do the contents get affixed together in consciousness in all the complex ways they’re supposed to? Via what rule does it work? One popular answer in the neuroscientific literature is that binding occurs via a process best described as “information transmission plus synchronization.”…

Assume this answer is true for a moment. According to neuroscience’s answer to the binding problem, if you synchronize different parts of the brain, you get a single consciousness bound together. So following the idea’s logic: if you synchronized different people, what do you get? Is it not at least imaginable you could get some sort of experience that goes beyond any individual person’s consciousness? A group mind?

… In occult practices, such joint ritual and concentration has traditionally been the way to summon an egregore—the occult term for a psychic entity much like a group mind.

In both the occult conception of egregores and a proposed solution to the binding problem, synchronization and information transmission leads to a unified mind. So, Erik asks, where do we find egregores today? Social media.

I think it’s worth looking around in our culture and our technology for where these forces [synchronization and information transmitting] are most at play. A certain answer springs to mind, which is that the place where we moderns are most synchronized while also transmitting the most information is not at football stadiums or in concert hall, but via our screens. Which would imply…

It’s undeniable that social media does feel very “mind-like” to interact with, in a way that (again, just how it feels) goes beyond the minds of the individuals. E.g., on social media there’s clearly a window of attention (“the current thing”), and as a network it can distribute tasks and ideas and come to conclusions, at least of a sort. Debates are considered, then are over, as played out as an already-handled thought. At its best this aspect of social media is joy to experience, the information so pertinent, the vibes so high. At its worse we call it “online mobs” or “cancel culture.”

Do group minds actually exist, though? One argument that they do is from equivalence to human minds.

The first common argument for group minds is the argument from equivalence. I.e., a neuron is a very efficient and elegant way to transmit information. But one can transmit information with all sorts of things. There’s nothing supernatural about neurons. So could not an individual ant act much like a single neuron in an ant colony? And if you find it impossible to believe that an ant colony might be conscious, that it couldn’t emerge from pheromone trails and the collective little internal decisions of ants—if you find the idea of a conscious smell ridiculous—you have to then imagine opening up a human’s head and zooming in to neurons firing their action potentials, and explain why the same skepticism wouldn’t apply to our little cells that just puff vesicles filled with molecules at each other.

One can go further. What if, as philosopher of mind Ned Block has asked, each citizen of China devoted themselves to carrying out the individual signaling of a neuron? This would then create a “China brain” which mimicked in functionality a real brain (although you would need about two more orders of magnitude to get close to approximating a full human brain in terms of numbers of neurons/citizens). There would be, at least functionally, an equivalence.

Erik spends a long time discussing how philosophy of mind applies to group minds. We’ll skip this, though I encourage you to read his piece if you’re interested in this. He ends with this:

At a personal level perhaps it’s worth remembering that those feelings of outrage—you know the kind, the ones that fill you with such anger you just have to speak out right now, the kind where you’re summoned as if by strings to contribute your little piping neuronal voice to that huge ongoing mind of the internet—those feelings could not be yours at all. Rather, they might just be a glimpse of something larger and darker passing like a giant out of sight.

Egregores: manipulative higher organisms

Michael Smith (Valentine on LW) writes (and notice how certain themes are beginning to repeat here):

I think the world makes more sense if we recognize humans aren’t on the top of the food chain.

We mostly don’t see this clearly, kind of like ants don’t clearly see anteaters. They know something is wrong, and they rush around trying to deal with it, but it’s not like any ant recognizes the predator in much more detail than “threat”.

There’s a whole type of living being “above” us the way animals are “above” ants.

Esoteric traditions sometimes call these creatures “egregores”…

I often refer to them as “memes” — although “memeplex” might be more accurate. Self-preserving clusters of memes…

What’s the medium? What’s the analog of molecules or code?

Well, it’s patterns of behavior, thought, and attention.

Some egregores benefit from manipulating our emotions and thoughts in negative ways. By doing so, they can “capture” us.

Many of the predatory egregores do not want us functioning naturally. They intentionally disrupt us. They lean heavily on systematized trauma and threat responses. They want to keep us scared, or angry, or exhausted, or hopeless.

And it works in part because we have a hard time noticing the true origin of these drives. We rehearse the reasons we hear and think of, and learn how to point fingers at an outgroup as bad or inferior or threatening…

…and then over the course of years or decades we find ourselves having been chess pieces in a game we weren’t really playing. Something else was playing us. History flowing through us in arcs much, much larger than we’re accustomed to seeing.

I mean, at this point you’ve probably noticed at least one person who used to be close to you who has “lost it”. Who clearly believes falsehoods while insisting that you’re the one who’s confused.

That’s what predation at the egregore level looks like. Ideological capture. People’s lifeforce poured into sustaining an idea cluster that has possessed them.

Flat Earth, “plandemic” conspiracies, blind trust in demonstrably untrustworthy authorities, “cancel culture”, Q-Anon…

…no matter where you stand on these or other controversial issues, I hope you can see a common thread of madness.

That’s the zombie virus. The anteaters. Our cordyceps.

The upshot of this all is that we can actually come to understand what’s going on.

But even beyond this, as humans and not ants, we have an opportunity:

We can come to see, understand, and touch this level “above” us.

Synthesis

[todo]

Footnotes

-

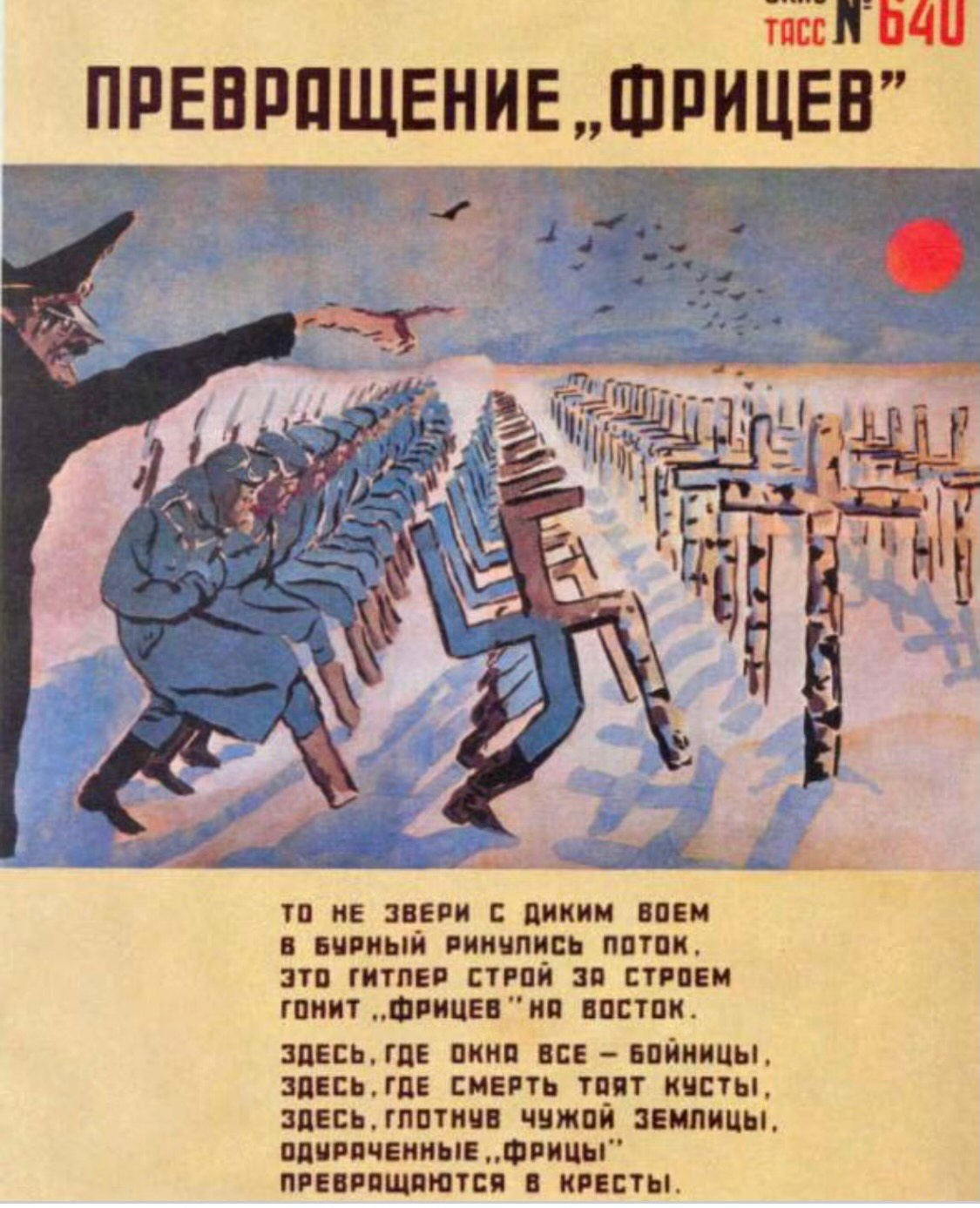

Yes, this image again. From a book review of Dostoevsky’s novel Demons, which will be quoted from later in the main post. The Futurama brain slug image and the Egregore-shoggoth image that will come later in the post also come from this book review. ↩

-

Bacon finishes this quote with a point I think is wrong: “Some minds (e.g. those that are dominated by one idea or set of ideas, perhaps a religious or political ideology) provide poor habitat and are avoided by all but the most desperate ideas (e.g. irrational and harmful ideas that can’t find a home elsewhere—this is why conspiracy theories and hateful ideologies tend to congregate in the same minds).” I think all ideas are basically looking for a home in every mind — it’s not like an idea can only live in one place. If it is indeed true that conspiracy theories and hateful ideologies tend to congregate in the same minds — and I’m not sure how strong that effect is — then it’s for reasons different than “they can’t find a home elsewhere.” ↩

-

Mr. Psmith finishes this section with: “Sometime in the mid-19th century, an egregore was born in the Russian Empire. It went by a thousand different names — among them: anarchism, communism, nihilism, democracy. What’s that? Those four ideologies are completely opposed to one another? That’s the entire point! It wasn’t actually any of those things, it was an egregore, its true name was something like Melkhorbalai or Uztaa-Binoreth. It wore those other names like skins when it was convenient to do so, which is why in the real life history of 19th century Russia we see countless examples of individuals switching between communism, anarchism, and democracy like they were flavors of ice cream. The egregore wanted none of these things: it wanted to grow, to spread, to manifest itself into this reality. Madly, it willed destruction, and the more destruction it caused the stronger it got, and the easier further destruction became, a runaway exothermic reaction endlessly feeding on itself. So the reformist zeal of the 1840s became Nechayev’s insane nihilism of the 1870s, then the even more insane terrorism of 1900-1917 with which I opened this review, until finally, strengthened by half a century of blood sacrifice, that rough beast slouched towards St. Petersburg to be born. The trauma of that birth ripped apart first Russia, then Europe, then it almost ate the rest of the world too.” I think this conception of egregore is a little confusing ontologically, which is why I didn’t include it in the main post. ↩

-

For more discussion on the concept and definition, see this post. ↩

-

Source: WW2 propaganda poster “Transformation of the Fritz”. (“Fritz” is a derogatory term for Germans.) ↩